The Unbelievable Skepticism of the Amazing Randi

A few minutes before 8 o’clock one Sunday evening last July, around 600 people crowded into the main conference hall of the South Point casino in Las Vegas. After taking their seats on red-velvet upholstered chairs, they chattered noisily as they awaited the start of the Million Dollar Challenge. When Fei Wang, a 32-year-old Chinese salesman, stepped onto the stage, they fell silent. Wang had a shaved head and steel-framed glasses. He wore a polo shirt, denim shorts and socks. He claimed to have a peculiar talent: from his right hand, he could transmit a mysterious force a distance of three feet, unhindered by wood, metal, plastic or cardboard. The energy, he said, could be felt by others as heat, pressure, magnetism or simply “an indescribable change.” Tonight, if he could demonstrate the existence of his ability under scientific test conditions, he stood to win $1 million.

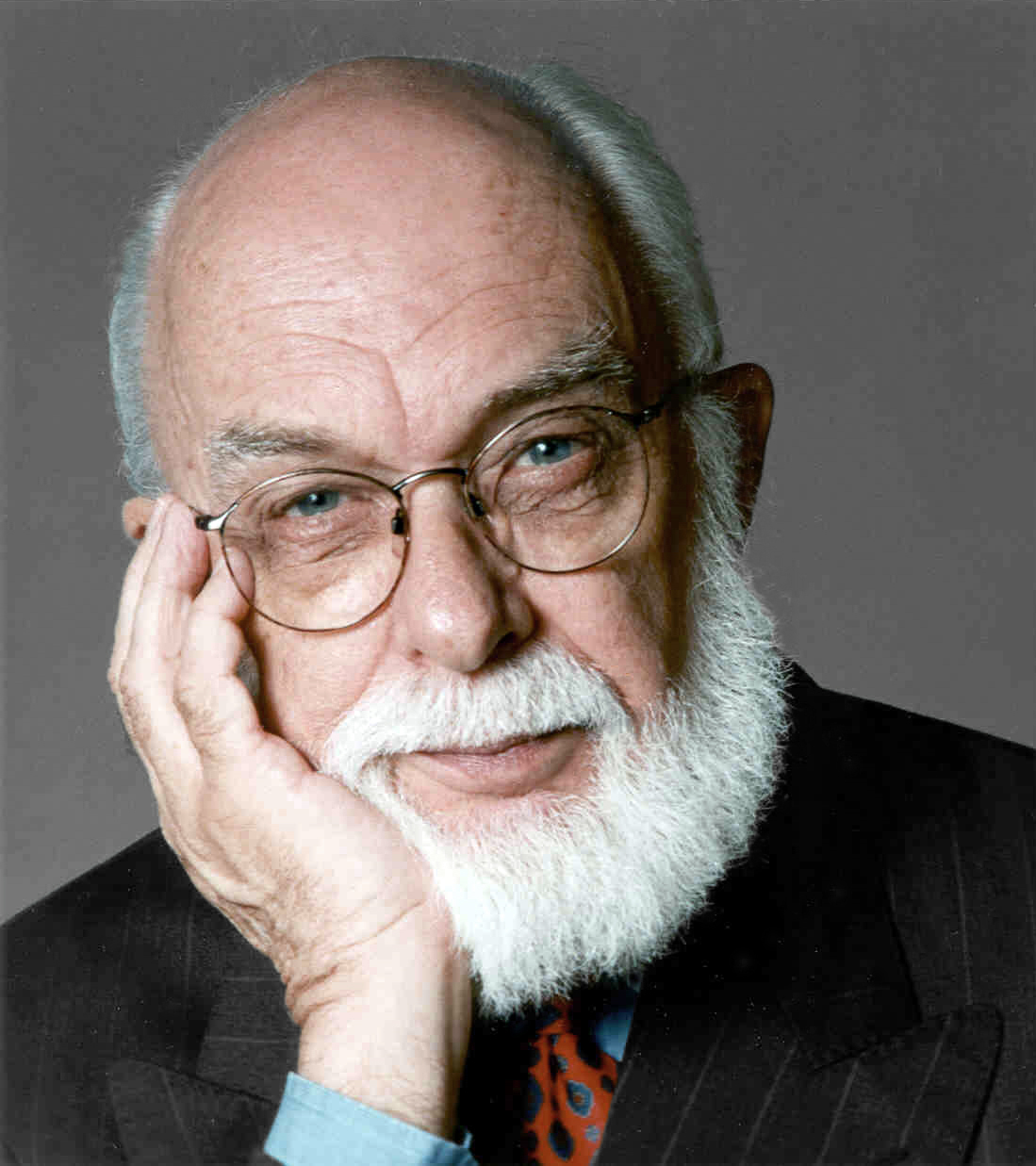

The Million Dollar Challenge was the climax of the Amazing Meeting, or TAM, an annual weekend-long conference for skeptics that was created by a magician named the Amazing Randi in 2003. Randi, a slight, gnomish figure with a bald head and frothy white beard, was presiding from the front row, a cane topped with a polished silver skull between his legs. He drummed his fingers on the table in front of him. The Challenge organizers had spent weeks negotiating with Wang and fine-tuning the protocol for the evening’s test. A succession of nine blindfolded subjects would come onstage and place their hands in a cardboard box. From behind a curtain, Wang would transmit his energy into the box. If the subjects could successfully detect Wang’s energy on eight out of nine occasions, the trial would confirm Wang’s psychic power. “I think he’ll get four or five,” Randi told me. “That’s my bet.”

In this excerpt from the forthcoming documentary film “An Honest Liar,” James Randi explains how Harry Houdini inspired him to also become a famed magician and escape artist. Video by Justin Weinstein and Tyler Measom on Publish Date November 7, 2014.

The Challenge began with the solemnity of a murder trial. A young woman in a short black dress stood at the edge of the stage, preparing to mark down the results on a chart mounted on an easel. The first subject, a heavyset blond woman in flip-flops, stepped up and placed her hands in the box. After two minutes, she was followed by a second woman who had a blue streak in her hair and, like the first, looked mildly nonplused by the proceedings. Each failed to detect the mystic force. “Which means, at this point, we are done,” the M.C. announced. With two failures in a row, it was impossible for Wang to succeed. The Million Dollar Challenge was already over.

Stepping out from behind the curtain, Wang stood center stage, wearing an expression of numb shock, like a toddler who has just dropped his ice cream in the sand. He was at a loss to explain what had gone wrong; his tests with a paranormal society in Boston had all succeeded. Nothing could convince him that he didn’t possess supernatural powers. “This energy is mysterious,” he told the audience. “It is not God.” He said he would be back in a year, to try again.

After Wang left the stage, Randi, who is 86, told me he was glad it was all over. For almost 60 years, he has been offering up a cash reward to anyone who could demonstrate scientific evidence of paranormal activity, and no one had ever received a single penny.

But he hates to see them lose, he said. “They’re always rationalizing,” Randi told me as we walked to dinner at the casino steakhouse. “There are always reasons prevailing why they can’t do it. They call it the resilience of the duped. It’s with intense regret that you watch them go down the tubes.”

The day before the challenge, Randi was wandering the halls of the casino, posing for snapshots and signing autographs. The convention began in 2003 in Fort Lauderdale, with 150 people in attendance, including staff. This year, it attracted more than 1,000 skeptics from as far away as South Africa and Japan. Often male and middle-aged, and frequently wearing ponytails or Tevas or novelty slogan T-shirts (product of evolution; stop making stupid people famous; atheist), they came to genuflect before their idol, drawn by both his legendary feats as an illusionist and his renown as an icon of global skepticism.

One fan, in his early 20s, with a thick mop of dark hair, introduced himself with, “So, I read that you spent 55 minutes in a block of ice.”

“A cinch,” Randi replied.

Ajay Appaden was 25 and had come from the Indian city Cochin. He was attending the conference for the second year with the help of a travel grant from the James Randi Educational Foundation (JREF), which was established with donations from the Internet pioneer Rick Adams and Johnny Carson. In addition to offering grants, JREF holds the $1 million in bonds that back the challenge, and pays Randi’s annual $200,000 salary.

Raised as a Catholic, Appaden told me that he discovered Randi in 2010, when he watched the magician in an online TED talk discussing homeopathy. At the time Appaden was a student at a Christian college, struggling with his faith; two years later, during Randi’s first visit to India, he took a 13-hour bus ride across the country to see Randi in person. “It literally changed my life,” he told me, and explained that he now hopes to help teach skepticism in Indian schools.

The magician looked small and frail, lost in the folds of his striped dress shirt, leaning on his cane, but he mugged gamely for every acolyte. For many of his most zealous followers, the opportunity to meet Randi at TAM may be as close as they will ever come to a religious experience. “It’s an obligation, it’s a very heavy obligation,” he said. “I can’t stand one person being turned away and not being given the same attention that others have been given.”

A few days before the conference, I visited Randi at his home, in Plantation, Fla. The modest octagonal house was almost hidden from the street by a lush garden of finger palms, elephant ears and paperbark trees. As we sat upstairs, surrounded by some 4,000 books — arranged alphabetically by subject, from alchemy, astrology, Atlantis and the Bermuda Triangle to tarot, U.F.O.s and witchcraft — he said that he disliked being called a debunker. He prefers to describe himself as a scientific investigator. He elaborated: “Because if I were to start out saying, ‘This is not true, and I’m going to prove it’s not true,’ that means I’ve made up my mind in advance. So every project that comes to my attention, I say, ‘I just don’t know what I’m going to find out.’ That may end up — and usually it does end up — as a complete debunking. But I don’t set out to debunk it.”

Born Randall James Zwinge in 1928, Randi began performing as a teenager in the 1940s, touring with a carnival and working table to table in the nightclubs of his native Toronto. Billed as The Great Randall: Telepath, he had a mind-reading act, and also specialized in telling the future. In 1949 he made local headlines for a trick in which he appeared to predict the outcome of the World Series a week before it happened, writing the result down, sealing it an envelope and giving it to a lawyer who opened and read it to the press after the series concluded. But no matter how many times he assured his audiences that such stunts were a result of subterfuge and legerdemain, he found there were always believers. They came up to him in the street and asked him for stock tips; when he insisted that he was just a magician, they nodded — but winked and whispered that they knew he was truly psychic. Once he understood the power he had over his audience, and how easily he could exploit their belief in the supernatural to make money, it frightened him: “To have deceived people like that .?.?. that’s a terrible feeling,” he said.

Once Randi understood the power he had over his audience, it frightened him: ‘To have deceived people like that .?.?. that’s a terrible feeling.’

He turned instead to escapology — as The Amazing Randi: The Man No Jail Can Hold — and feats of endurance. He broke a record for his 55-minute stint encased in ice, and bested the time his hero Houdini had spent trapped in a coffin on the bottom of the swimming pool at the Hotel Shelton in Manhattan. But Randi never forgot the believers, and how susceptible they were to exploitation by those who lacked his scruples. And so, as his reputation as a magician grew, he also began to campaign against spiritualists and psychics. In 1964, as a guest on a radio talk show, he offered $1,000 of his own money in a challenge to anyone who could show scientific evidence of supernatural powers. Soon afterward, he began broadcasting his own national radio show dedicated to discussion of the paranormal. He bought a small house in Rumson, N.J., and installed a sign outside that announced randi — charlatan. He lived there alone, with a pair of talking birds and a kinkajou named Sam. Although Randi had known he was gay since he was a teenager, he kept that to himself. “I had to conceal it, you know,” he told me. “They wouldn’t have had a known homosexual working in the radio station. This was a day when you had to keep it completely hidden.”

During the late ’60s and early ’70s, popular interest in the paranormal grew: There was a fascination with extrasensory perception and the Bermuda Triangle and best sellers like “Chariots of the Gods,” which claimed Earth’s ancient civilizations were visited by aliens. There were mystics, mind-readers and psychic surgeons, who were said to be able to extract tumors from their patients using only their bare hands — and without leaving a mark. Randi continued on his crusade. Few of his fellow illusionists were interested in exposing the way that conjuring tricks were used to dupe gullible audiences into believing in psychic abilities. “Everybody else just kind of rolled their eyes,” Penn Jillette, a good friend of Randi’s, told me. “’Why is Randi spending all this time doing this? We all know there is no ESP. It’s just stupid people believe it, and that’s fine.’ ”

Randi kept up his $1,000 challenge — and eventually increased it to $10,000 — but found few takers. Then in 1973, he met the nemesis who would define his struggle: Uri Geller, who had recently arrived in the United States from Israel. Geller was a charismatic 26-year-old former paratrooper who performed mind-reading feats similar to those with which Randi baffled audiences as a young mentalist. But Geller said that his powers were real and also claimed to have psychokinetic abilities: He could bend spoons, he said, using only his mind. His supposed gifts were studied by a pair of parapsychology researchers at Stanford Research Institute, who were persuaded that some of them, at least, were genuine. Randi told me that he met Geller soon afterward. “Very flamboyant,” he recalled venomously. “Very charming. Likable, beautiful, affectionate, genuine, forward-going, Handsome — everything!” His manner, Randi explained, was the key to the techniques employed by Geller and others like him. “That’s why they call them con men. Because they gain the confidence of the victim — and then they fool ‘em.”

Geller provided Randi with an archenemy in a show-business battle royale pitting science against faith, skepticism against belief. Their vendetta would endure for decades and bring them both international celebrity. Recognizing that the psychic’s paranormal feats were a result of conjuring tricks — directing attention elsewhere while he bent spoons using brute force, peeking through his fingers during mind-reading stunts — Randi helped Time magazine with an exposé of Geller. Soon afterward, when Geller was invited to appear on “The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson,” the producers approached Randi, who had been a frequent guest, to help them ensure that Geller could employ no tricks during his appearance. Randi gave Carson’s prop men advice on how to prepare for the taping, and the result was a legendary immolation, in which Geller offered up flustered excuses to his host as his abilities failed him again and again. “I sat there for 22 minutes, humiliated,” Geller told me, when I spoke to him in September. “I went back to my hotel, devastated. I was about to pack up the next day and go back to Tel Aviv. I thought, That’s it — I’m destroyed.” But to Geller’s astonishment, he was immediately booked on “The Merv Griffin Show.” He was on his way to becoming a paranormal superstar. “That Johnny Carson show made Uri Geller,” Geller said. To an enthusiastically trusting public, his failure only made his gifts seem more real: If he were performing magic tricks, they would surely work every time.

Randi decided Geller must be stopped. He approached Ray Hyman, a psychologist who had observed the tests of Geller’s ability at Stanford and thought them slipshod, and suggested they create an organization dedicated to combating pseudoscience. In 1976, together with Martin Gardner, a Scientific American columnist whose writing had helped hone Hyman’s and Randi’s skepticism, they formed the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal. Csicop, as it became known, was funded by donations and by sales of a new magazine, which became The Skeptical Inquirer. Randi, Hyman and Gardner and the secular humanist philosopher Paul Kurtz took seats on the executive board, with Isaac Asimov and Carl Sagan joining as founding members. Soon Randi was traveling across the globe, often “as the ambassador” of Csicop, Hyman told me recently, “the face of the skeptical movement all over the world.”

In his new role as a paranormal investigator, in books and on TV shows, Randi debunked everything from fairies to telekinesis. But he also stalked Geller around the chat-show circuit for years, denouncing him as a fraud and duplicating his feats by levering spoons and keys against the furniture while nobody was looking. In 1975, Randi published “The Magic of Uri Geller,” a sarcastic but exhaustive examination of the psychic’s techniques, in which he argued that any scientist investigating the paranormal should seek the advice of a conjurer before conducting serious research. The campaign helped make them both more famous than ever. Even today, Geller credits Randi with helping him become a psychic phenomenon — “My most influential and important publicist,” as Geller described him to me.

In 1989, Randi and Geller were booked to appear together on a TV special, “Exploring Psychic Powers, Live!” According to Randi, before the broadcast, Geller pulled him into his dressing room and offered to end the feud. “There’s no way that we are going to make peace until you level with your audiences,” Randi replied. “Until you say that you are a magician like the rest of us, and that you don’t have supernatural powers.” Geller refused. (Geller says he does not recall the incident.) Soon after, Geller brought the first of several libel actions against Csicop and Randi — who, among other things, had characterized him as a sociopath and suggested his psychic feats had been learned from the backs of cereal boxes. Geller’s suits in the United States were eventually dismissed. But the legal costs of fighting the cases were overwhelming, and Randi went through almost all of a MacArthur Foundation grant of $272,000 awarded to him in 1986 for his paranormal investigations. Finally, the struggle with Geller even cost Randi his place in Csicop; when Paul Kurtz told him it had become too expensive to keep going after such a litigious target, and demanded he stop discussing Geller in public, Randi resigned in fury.

Geller, who now lives in a large house beside the Thames River in England, says he long ago put the feud with Randi behind him. He claims to have used his show-business career as a cover for paranormal work on behalf of Mossad and the C.I.A., but he no longer calls himself a psychic. “I changed my title to ‘mystifier,’ ” he told me. “And I love it — because it means nothing.” But Randi’s contempt for him still burns brightly. “He knows he is deceiving these people — individuals, in most cases — and he doesn’t care what damage he does to them,” Randi said. “They depend on the paranormal after they have met Geller, and you cannot talk them out of it. And that has crippled them for life.”

Early one morning last summer, on a visit to Randi’s house in Florida, I drew up outside a few minutes later than we had agreed. Randi, wearing a canary yellow sweatshirt, was waiting at the front door, holding his watch in his hand. “You’re late!” he barked, and it was hard to tell if he was joking. We sat down in the living room to talk, and Randi spent half an hour laboriously adjusting his watch, winding the hands to display the correct date. “I am a little bit obsessed with having the right time,” he said. “I’ve always been very, very, big on knowing what time it is. That’s one of my connections with reality.”

Randi has never smoked, taken narcotics or got drunk. “Because that can easily just fuzz the edges of my rationality, fuzz the edges of my reasoning powers,” he once said. “And I want to be as aware as I possibly can. That may mean giving up a lot of fantasies that might be comforting in some ways, but I’m willing to give that up in order to live in an actually real world.”

That fixation on science and the rational life — and a corresponding desire to crusade for the truth — has a long history among magicians. John Nevil Maskelyne, who founded a dynasty of English conjurers in 1855 and became a prolific inventor, began his career by exposing fraudulent spiritualists and reproducing their tricks. Houdini turned to debunking mediums in his middle age as his career as an escapologist went into decline. He offered his own $10,000 reward to any spiritualist who could perform a “miracle” he could not duplicate himself. Martin Gardner, whose book “Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science” is a founding text of modern skepticism, was also fascinated by magic, and became well known for his books explaining how many conjuring and mind-reading tricks rely upon strict laws of probability and number theory. Penn and Teller have since followed Randi down the path of conjurers who have become debunkers.

Randi now sees himself, like Einstein and Richard Dawkins, in the tradition of scientific skeptics. “Science gives you a standard to work against,” he said. “Science, after all, is simply a logical, rational and careful examination of the facts that nature presents to us.”

Although many modern skeptics continue to hold religious beliefs, and see no contradiction in embracing critical thinking and faith in God, Randi is not one of them. “I have always been an atheist,” he told me. “I think that religion is a very damaging philosophy — because it’s such a retreat from reality.”

When I asked him why he believed other people needed religion, Randi was at his most caustic.

“They need it because they’re weak,” he said. “And they fall for authority. They choose to believe it because it’s easy.”

In the 1980s, Randi turned his talent for deception to debunking the supernatural. He set out to expose New Age channelers, mediums who — on shows and in profitable public appearances — purported to be possessed by ancient spirits. One, JZ Knight, a former cable TV saleswoman, claimed to be the terrestrial mouthpiece of Ramtha, a 35,000-year-old warrior from Atlantis who could predict the future.

To show how credulous audiences could be in the face of such claims, in 1987 Randi collaborated with the Australian version of “60 Minutes.” He invented Carlos, a 2,000-year-old entity who, his publicity material stated, had last appeared in the body of a 12-year-old boy in Venezuela in 1900 but had now returned to manifest himself through a young American artist named José Alvarez. He prepared to take Alvarez on a tour of Australia.

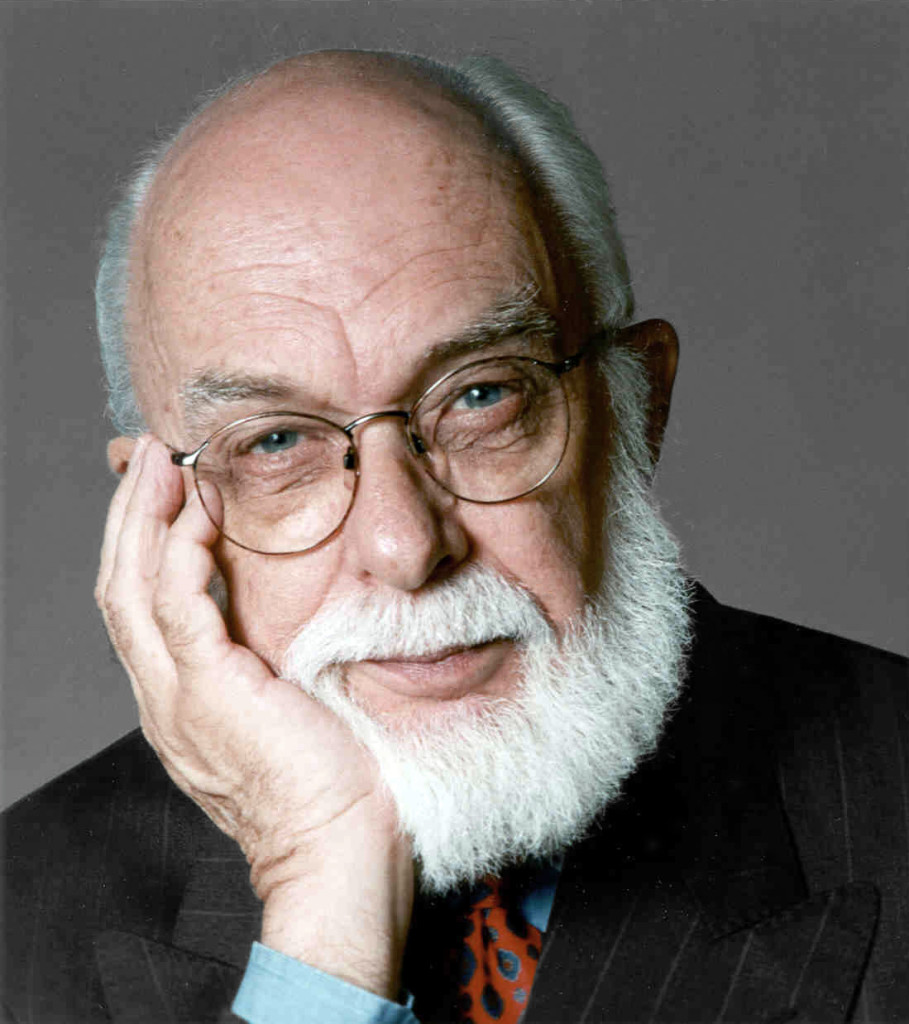

Alvarez, at the time a 25-year-old student at the Art Institute of Fort Lauderdale, was in fact Randi’s boyfriend, and also his assistant. They met the year before in a Fort Lauderdale public library, where Alvarez was seeking visual references for a ceramics project. Randi, who had only recently relocated to Florida from New Jersey, struck up a conversation with him. They talked all afternoon and moved in together soon afterward.

Randi coached Alvarez carefully for his role as Carlos, rehearsing him through mock news conferences and TV appearances. He taught him how to squeeze a Ping-Pong ball in his armpit so that his pulse would appear to slow as he became “possessed” — “an old, old thing from Boy Scout camps,” Randi told me. Before the trip, Randi sent out press kits to Australian TV networks and newspapers, filled with reports charting the apparently sensational — but fictional — progress of Carlos across the United States.

Soon after they arrived in February 1988, Alvarez was booked on many of the country’s leading TV shows. Through an earpiece, Randi fed him answers to interview questions and the lines of doomsday prophecies. The climax of his tour was an appearance at the Sydney Opera House, after which the audience was invited to place orders for crystal artifacts, including the Tears of Carlos, priced at $500 each, and an Atlantis Crystal, offered at $14,000. Each proved popular — though Randi’s team never accepted any money for them.

When the hoax was revealed a few days later on “60 Minutes,” the Australian media was enraged at having been taken in; Randi countered that none of the journalists had bothered with even the most elementary fact-checking measures.

Afterward, Randi and Alvarez returned to Florida together, and Alvarez’s reputation as an artist blossomed. For the next 14 years, he toured the Carlos persona around the world as part of a performance piece, appearing onstage in Padua, Italy, and sitting for photographs on the Great Wall of China re-enacting the hoax. In 2002, the work Alvarez created from the Carlos episode was exhibited at the Whitney Biennial in New York.

Meanwhile, the establishment of the James Randi Educational Foundation in 1996 allowed Randi to continue his own pursuits with the foundation’s headquarters, a Spanish-style stucco building in Fort Lauderdale, as his base of operations. He created the Million Dollar Challenge and regularly wrote bulletins for the foundation’s website, where the message boards formed an online hub for skeptics worldwide. In recent years, he began making regular podcasts, and he also created his own YouTube channel to discuss everything from Nostradamus to cold fusion. In 2007, during his TED talk taking aim at quackery and fraud, Randi delighted his audience by gobbling an entire bottle of 32 Calms homeopathic sleeping tablets — which Randi speculated was certainly a fatal dose.

Disappointed by what he saw as the media’s indifference to the Million Dollar Challenge, that same year Randi revised the rules and announced a plan to take the challenge to high-profile psychics, including Sylvia Browne, John Edward and — once again — Uri Geller. None of them agreed to participate. He had more success in 2008, when he invited James McCormick, a British businessman, to take the challenge. McCormick had built equipment that could supposedly detect explosives from afar, which Randi recognized was simply a telescoping antenna swiveling on a plastic handle — a dowsing rod. Randi publicly offered the million-dollar prize to McCormick if he could prove that the device worked as claimed. McCormick, who was selling his product to security forces in the Middle East, never responded. But the British Police began an investigation, and last year McCormick was found guilty of fraud and sentenced to 10 years in prison, having sold at least $38 million worth of his miraculous device to the Iraqi government.

Randi with his partner of more than 25 years, the artist José Alvarez, at their Florida home. Credit Jeff Minton for The New York Times

Continue reading the main story

Recently, age and illness have begun to slow Randi down. In 2009, following chemotherapy for intestinal cancer, he presented the opening address at TAM from a wheelchair. Earlier this year, JREF’s Fort Lauderdale building was sold, and its reference library and collection of memorabilia were boxed up and relocated to Randi’s home. When I visited, many of the cartons remained unpacked; the portrait of Isaac Asimov that once hung above the fireplace in the JREF library was propped against a wall.

Randi was all but marooned in the house — he was forbidden to drive while he awaited cataract surgery — and Alvarez had been forced to surrender his driver’s license, after a series of events that began on Sept. 8, 2011. That morning there was a knock on the front door. When Randi opened it, a pair of federal agents stood before him. They asked to speak to Alvarez. Outside, Randi could see two unmarked S.U.V.s blocking the driveway and at least half a dozen agents surrounding the perimeter of the property. When Alvarez came downstairs from his room, the agents explained there was a problem. They wanted to talk to him about passport fraud. They cuffed him and took him out to the car. Randi was left alone in the house, holding business cards from State Department agents, who, Randi said, gave him instructions to wait 24 hours before calling them.

The agents took Alvarez directly to Broward County Jail, where he was photographed, issued a gray uniform and registered as FNU LNU: “first name unknown, last name unknown.” In an interview room at the jail, he told an agent everything: He had fled homophobic persecution in Venezuela and had come to the U.S. on a two-year student visa. He met Randi and knew he wanted to stay with him. But when his visa expired, there was no way to renew it. He said he was given the name and Social Security number of José Alvarez by a friend in a Fort Lauderdale nightclub, and used it to apply for a passport in 1987. Alvarez told the agent he was deeply sorry for the trouble he had caused the real Alvarez — who he believed was dead but turned out to be a teacher’s aide living in the Bronx. FNU LNU said his real name was Deyvi Orangel Peña Arteaga.

Charged with making a false statement in the application and use of a passport and aggravated identity theft, Peña faced a $250,000 fine, a sentence of up to 10 years in prison and deportation to Venezuela. After six weeks in jail, he was released on a $500,000 bond, and he subsequently agreed to plead guilty to a single charge of passport fraud. At a sentencing hearing in May 2012, the judge considered letters of support from Randi and Peña’s friends from the world of art, science and entertainment, including Richard Dawkins and Penn Jillette, as well as from members of charities to which Peña had given his time and work. The judge considered Peña’s long relationship with Randi, and Randi’s failing health. He gave him a lenient sentence: time served, six months’ house arrest and 150 hours’ community service.

But Peña still had to contend with the immigration authorities. After the sentencing hearing, he had been home for five days when Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents appeared at the door. “Say goodbye,” they told him. Peña assured Randi he would be back that afternoon. He was taken to the Krome detention center in Miami, and remained there while his lawyer tried to find a way of keeping him in the United States. After two months of incarceration, Peña was finally released from Krome on the evening of Aug. 2, 2012, to find that Randi had spent half the day waiting outside the front gate for him. The couple were married in a ceremony in Washington the following summer.

Today, Peña remains on probation and no longer holds any identity documents except a Venezuelan passport with his birth name. United States immigration authorities have agreed not to deport him for now, but he has no formal immigration status in the United States: were he to leave the country, he would be unable to return. Since his arrest, Peña has not entirely shrugged off his former persona. He signs his paintings with the name he has exhibited under for 20 years — but now followed by his true initials, D.O.P.A.

Sometimes when Randi forgets himself, he still refers to his partner as José. Yet exactly how much Randi — the master of deception and misdirection — knew about his partner’s duplicity, and how complicit he may have been in it, is unclear. When Randi first met him in the Fort Lauderdale public library, it seems certain that Peña would have introduced himself by his real name: A profile of Randi published in The Toronto Star the following year describes the magician’s young assistant, named David Peña, struggling through La Guardia Airport with Randi’s luggage. When they traveled to Australia together for the “60 Minutes” stunt, Randi may have been masterminding a deception one level deeper than he ever acknowledged: Deyvi, pretending to be José, masquerading as Carlos, the 2,000-year-old spirit from Caracas. What followed might be the longest-running hoax of The Amazing Randi’s career.

When I asked Randi how much he knew about Peña’s true identity before the federal agents came to his door, he demurred, citing legal concerns. “This is something I don’t think I’d like to get into detailed discussion about,” Randi said. “Simply because it could prejudice our status in some way.”

When he was still a young man appearing in Toronto nightclubs and pretending to predict the future, Randall Zwinge created what he hoped would be his greatest trick. Each night before he went to bed, he wrote the date on the back of a business card along with the words “I, Randall Zwinge, will die today.” Then he signed it and placed it in his wallet. That way, if he were knocked down in the street or killed by a freak accident, whoever went through his effects would discover the most shocking prophecy he ever made. Zwinge kept at it for years. Each night, he tore up one card and wrote out a new one for the next day. But nothing fatal befell him; in the end, having wasted hundreds of business cards, he gave up in frustration. “I never got lucky,” he told me.

Since then, Randi has had several brushes with death. But nothing has shaken his steadfast rationalism: neither the heart attack he suffered in 2006, nor the cancer that followed. Nor, for that matter, did a conversation he had with Martin Gardner a few years before Gardner’s death in 2010, when his friend confessed to having chosen to believe in the possibility of an afterlife. “That really surprised me, because he was the rationalist supreme,” Randi recalled. “He said: ‘I don’t have any evidence for it, you have all the arguments on your side. But it brings me comfort.’ ”

Randi told me that he now feels mild trepidation each time he goes to sleep at night, and pleasant surprise that he wakes up in the morning. But he insists he does not need the sort of reassurance that Gardner sought in his own last days. “I wouldn’t have any comfort from it — because I wouldn’t believe in it,” he said. “Oh, no, I have no fear of my demise whatsoever. I really feel that sincerely.”

Most mornings, Randi is already awake at 7 o’clock, when Peña comes in to check on him; sometimes he’s up at 6. “I’ve got a lot of work to do, still,” he told me, “and I’ve got to make use of my viable time.” He is currently completing his 11th book, “A Magician in the Laboratory,” and spends several hours a day responding to emails from his desk in the chaotic-looking office he maintains upstairs. He Skypes with friends in China or Australia once a week. Peña likes to cook, and paints downstairs, beside the framed lithograph recalling the triumphs of the Man No Jail Can Hold. The couple have spent much of the last year traveling to film festivals and screenings across the United States, helping to promote a new documentary about Randi’s life, “An Honest Liar,” which will be released in February. Randi has been surprised by the response. “Standing ovations, the whole thing,” he told me.

In July last year, Randi came closer than ever to the end. He was hospitalized with aneurysms in his legs and needed surgery. Before the procedure began, the surgeon showed Peña scans of Randi’s circulatory system. “Very challenging, a very difficult situation,” the surgeon told him. “But he lived a good life.” The operation was supposed to take two hours, but it stretched to six and a half.

When Randi began to come to, heavily dosed with painkillers, he looked about him in confusion. There were nurses speaking in hushed voices. He began hallucinating. He was convinced that he was behind the curtain before a show and that the whispering he could hear was the audience coming in. The theater was full; he had to get onstage. He tried to look at his watch, but he found he didn’t have it on. He began to panic. When the hallucinations became intensely visual, Peña brought a pen and paper to the bedside. It could prove an important exercise in skeptical inquiry to record what Randi saw as he emerged from a state so close to death, one in which so many people sincerely believed they had glimpsed the other side. Randi scribbled away; his observations, Peña thought, might eventually make a great essay. Later, when the opiates and the anaesthetic wore off, Randi looked at the notes he had written.

They were indecipherable.

Adam Higginbotham is the author of “A Thousand Pounds of Dynamite,” published by The Atavist.

Pingback: The Unbelievable Skepticism of the Amazing Randi | Auto Magic